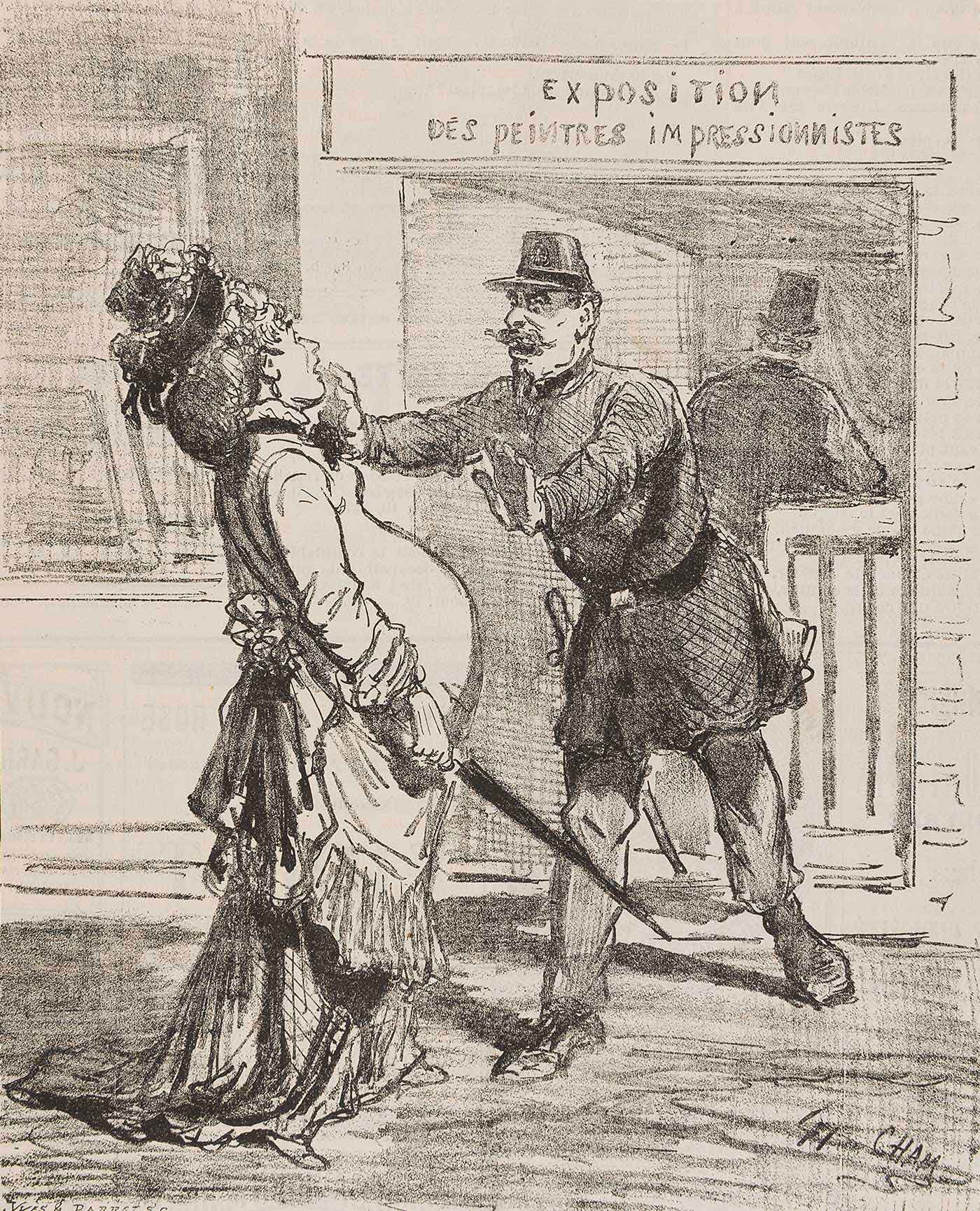

“MADAME, IT IS NOT ADVISABLE TO ENTER!”

In the latter half of the 19th century Impressionism roiled the French art world. The new movement broke with the rules established by the academies. Hence the jury of the Salon frequently rejected the works by the Impressionists.

The artists’ common idea was to capture the atmosphere of a moment in a painterly way. This aim went along with a method of painting, which the public was not accustomed to.

Apart from Claude Monet, artists like Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Alfred Sisley, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro and Berthe Morisot were important representatives of the new movement. The group’s name was inspired by the painting “Impression, Sunrise”, which Monet presented on the occasion of their first exhibition together in 1874.

Now what is this blotch? A bright moment.

Paul Bourget, 19051

THE STUDY OF LIGHT

Monet depicted the road to Chailly, which cuts directly through the Forest of Fontainebleau. There are no people in the work. He created the tension in the painting purely through the composition and the way he applied the paint. This work already shows Impressionist ideas, which were to become characteristic of his style. Monet strove to capture the light of a particular place at a particular time in a way that was true to his momentary impression. Atmosphere becomes more important than the accuracy of detail.

In order to quickly capture a moment, the artists worked with broad flat brushes – a shape of paintbrush that had been introduced only recently, when the invention of the metal ferrule had made it possible.

THE FILTERED GAZE

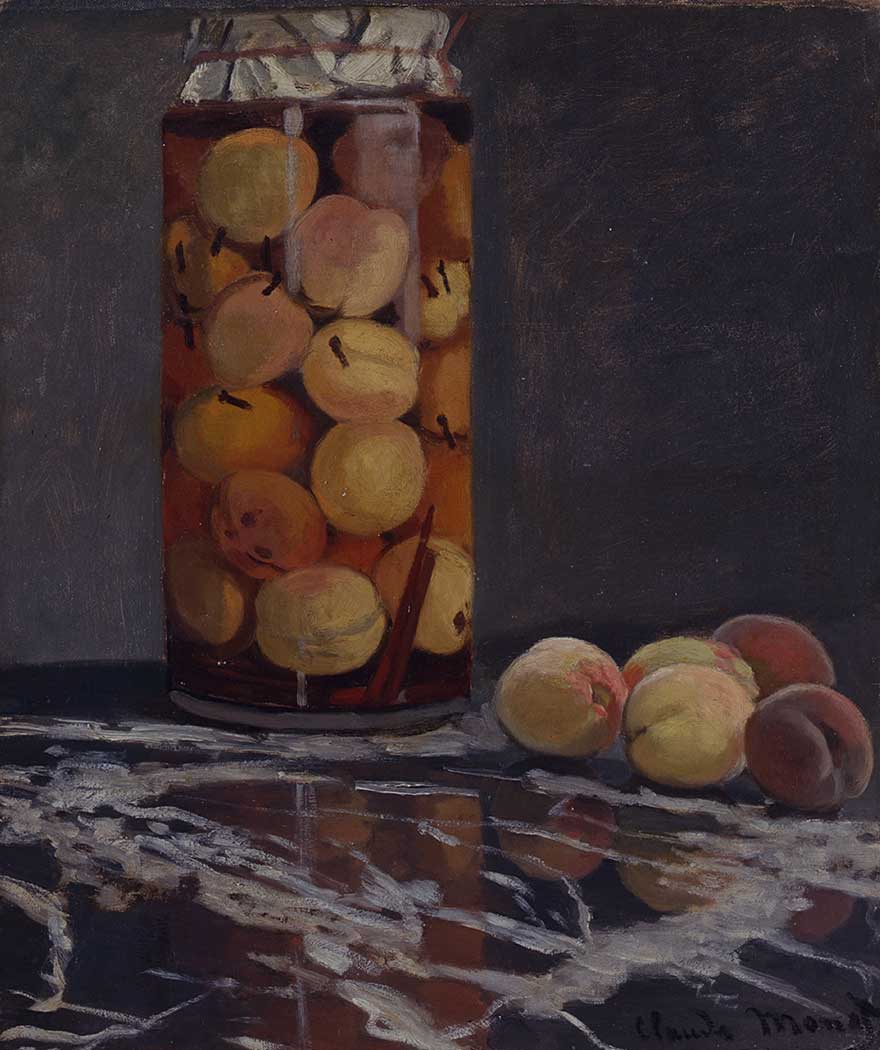

The still live shows the fruit at different stages: as fresh fruit, preserved and reflected by the marble. To the viewer’s eye the appearance of the objects changes. Their optical appearance is influenced by the respective filter – glass, liquid and reflection.

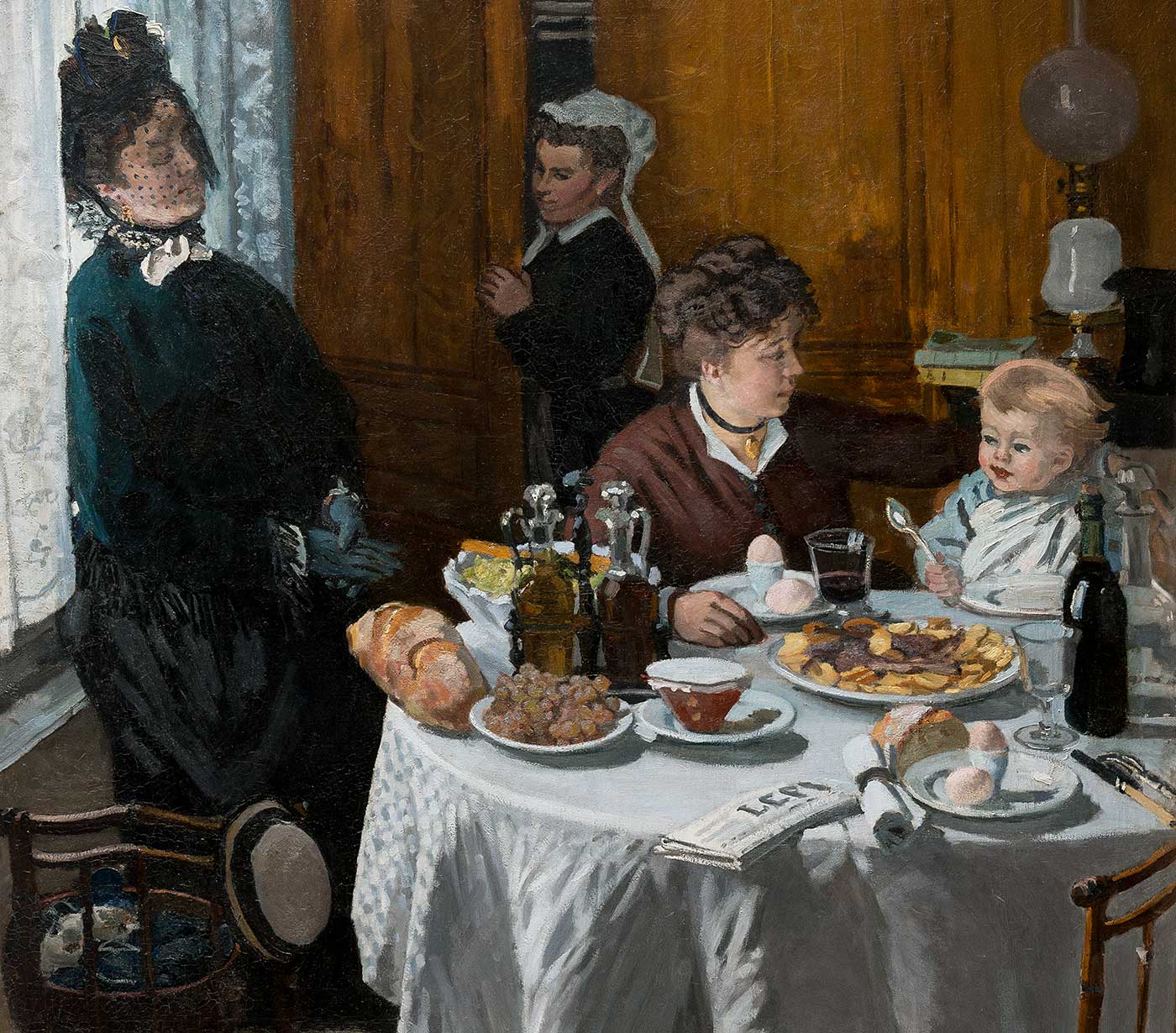

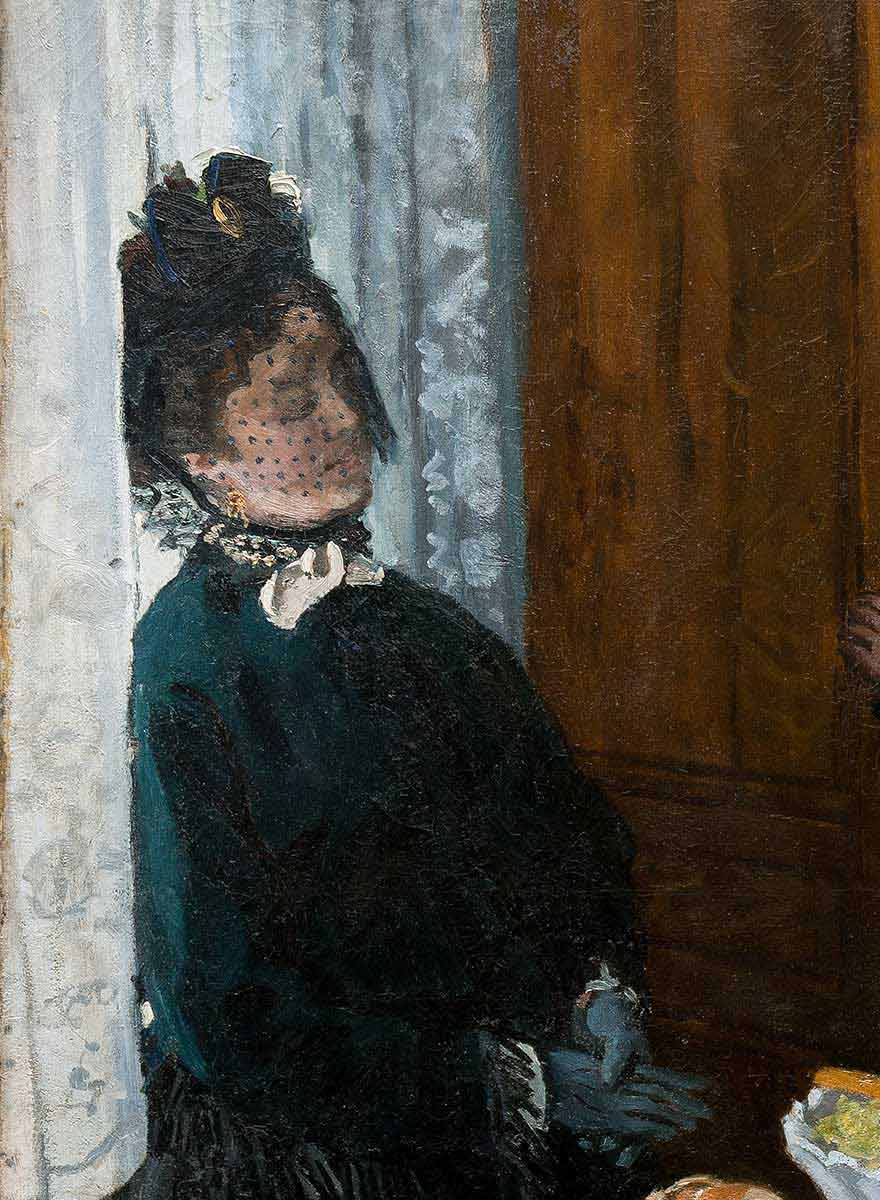

LUNCH AT MONET’S

History painting – traditionally the most highly regarded genre in painting – dramatically staged religious, mythological or historical themes seeking to inspire great feelings and to instil a superior moral.

In his painting “The Luncheon” Monet broke with this order of genres: composition and method of painting show that he took particular care to represent the objects on the table. Thus he composed a still live with an ordinary scene of daily life.

Unlike history painting, still lives and genre scenes were the least regarded genres of painting – and were traditionally presented on a small scale. The monumental measures of “The Luncheon” upgrades the quotidian.

Monet intended to submit “The Luncheon” to the Salon. Its size would have made it stand out in the presentation, where the art works were often presented one above the other several meters high. However, the work was rejected. In 1874 he presented it at the first Impressionist exhibition.

FROM THE INSIDE TO THE OUTSIDE

Again a dining table is placed in the foreground of the composition; however, this time Monet is taking the scene outside. The persons have already left the table and are leisurely strolling through the sunny garden. In comparison with “The Luncheon” they are receding into the background. Everything in the painting is subordinate to the mood of the moment.

In terms of subject, Monet systematically draws on “The Luncheon” simply presenting the same subject at another point in time. His “panneau decoratif” (decorative panel), which he calls his painting, makes do without a narrative. Instead the focus is on the atmosphere. Monet even dares placing an empty space at the centre of the painting – represented in shimmering colours.

THE WORLD IS SET IN MOTION

REFLECTIONS ON THE WATER

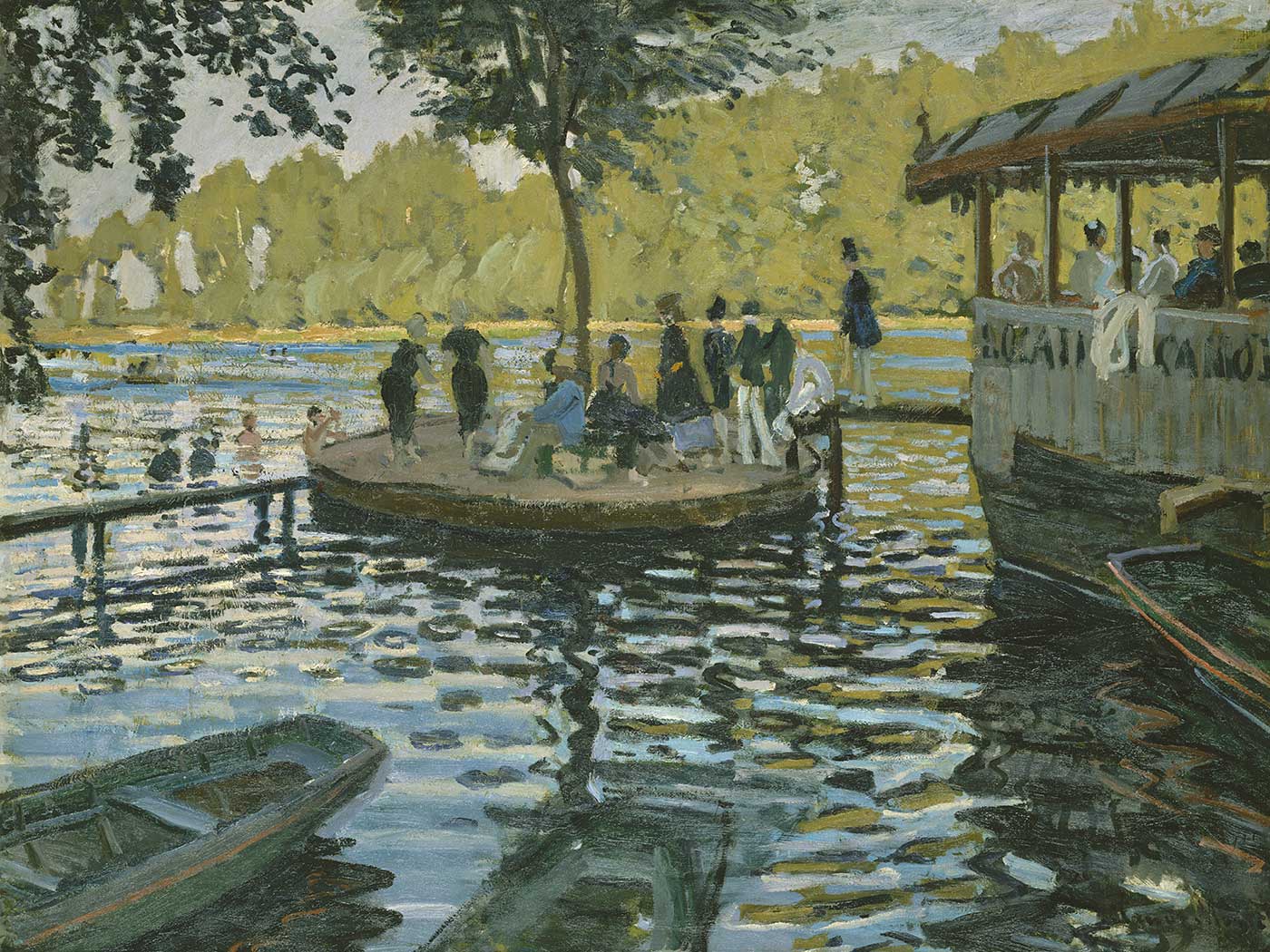

Neither the floating café, nor the bathers, but the reflections on the water were at the focus. The undulation captured in rough brushstrokes is at odds with the clear structure of the composition, where the boats and the jetty point towards the centre of the painting.

The building and the roughly outlined people can hardly be made out in the reflections on the surface of the water. The reflections seem to be independent from their surroundings.

A SEABREEZE

The sea is barely visible. It is the flying flag that makes the viewer intuit the murmur of the waves. Single figures with hats and parasols are leisurely promenading along the sea front at Trouville. To the right the Hôtel des Roches Noires reaches into the blue sky.

In June 1870 Monet had married his lover Camille Doncieux. Together with their son, they spent the summer in the popular holiday resort Trouville – however, not at this hotel, but in more modest accommodation. The peaceful atmosphere of the painting does not contain the slightest hint of the imminent Franco-German War.

FROM AFAR

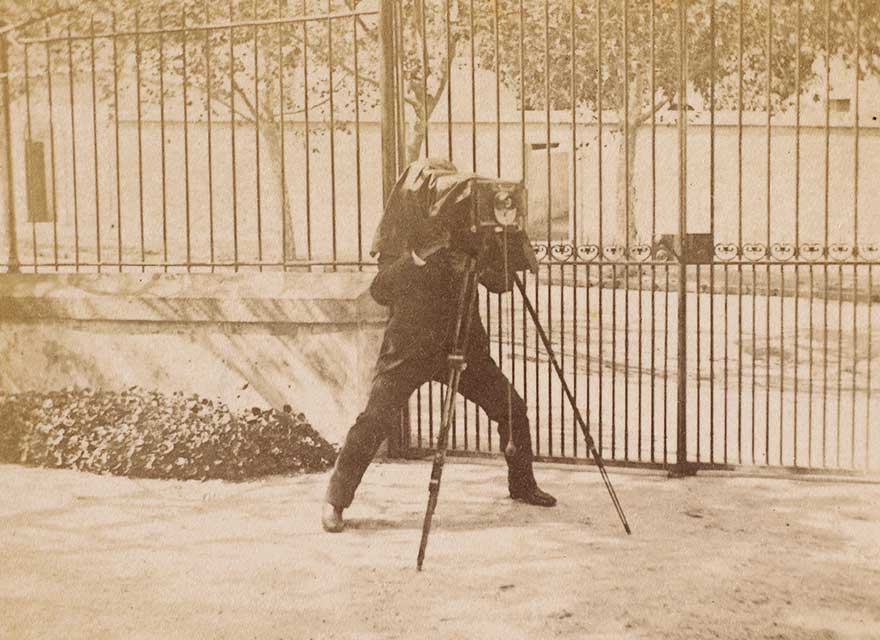

In wintery conditions countless people are bustling along the boulevard des Capucines. Their painterly dissolved bodies are reminiscent of the shadows of movement in a blurry photograph. But the immobile items, such as trees and houses, too merge with this diffuse field of colour.

Monet painted the boulevard des Capucines from the second floor of the house at No. 35. The broad boulevards, which had recently been constructed, offered the Impressionists a new experience of seeing. The distance to the street offered an overview over what was going on on the one hand; on the other hand the blurring of the figures betrays that the detail is lost in the overall impression.

FLOOD OF COLOUR IN A SEA OF FLOWERS

He said he wished he had been born blind and then had suddenly gained his sight so that he could have begun to paint in this way without knowing what the objects were that he saw before him.

Lilla Cabot Perry on Claude Monet, 19273

A MOMENT OF CALM

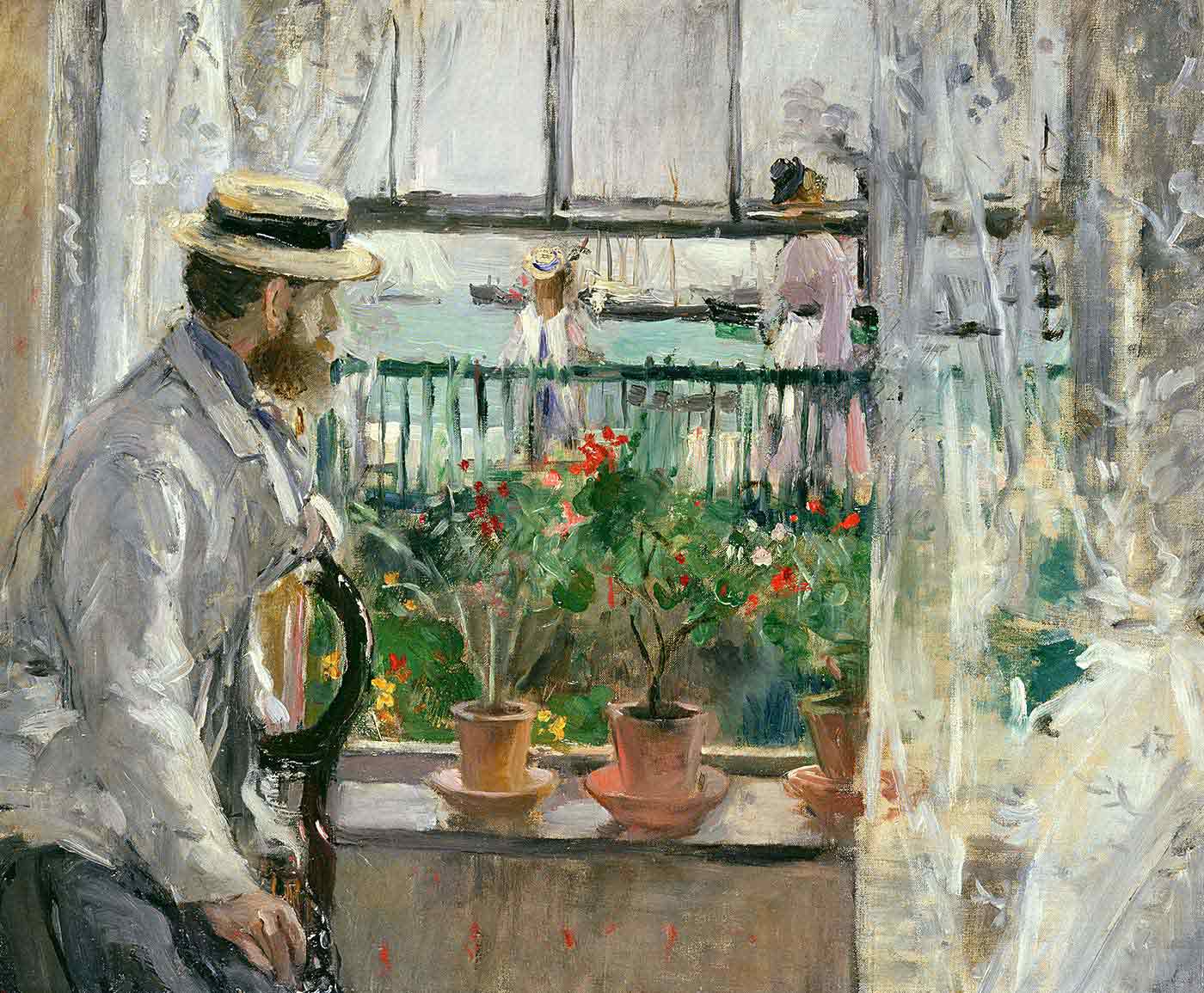

THE APPEAL OF THE CONCEALED

The artist is creating tension in a sophisticated way, directing the gaze into the depth of the painting via several layers. A man is peeking through a gap between window frame and fence. The succession of looks leads him outside on to the girl and the woman and finally to the boats in the distance.

The man’s gaze out of the window is the only connection of inside and outside. By placing the man inside and the women outside, Morisot is inverting the traditional role of the sexes, where the public realm was the space assigned to the male and the interior the space of the female.

Mr. Monet wanted to show us the various aspects of Saint-Lazare station with trains arriving and departing. Unfortunately the thick smoke exuded by the canvas prevented us from looking.

A critic of the third Impressionist-exhibition, 18774

SMOKE OBSCURES THE VIEW

AT SAINT-LAZARE STATION

A round traffic sign creates a barrier right at the centre of the painting. The area of Saint-Lazare station seems out of focus – as if perceived from a moving train. In addition the view is obscured by thick smoke billowing out of steam locomotives.

Individual shapes can barely be discerned behind a veil of smoke. Monet almost makes the objects disappear completely in the clouds. The specific materiality of the items becomes secondary. The focus lies on the location’s atmosphere.

STRUCK WITH SORROW

A painful moment for Monet: in 1879, following a serious illness, his wife Camille died at the young age of only 32 years. Fleeting brushstrokes depict her on her deathbed. Camille almost disappears behind a veil of shimmering hues of colour.

They say that Monet was taken aback by the way he painted her. At this emotional time he automatically distanced himself from what was happening and only observed the changing tones of colour; he followed the tragic scene with the painter’s “innocent eye”. The painterly aspect triumphs over the content.

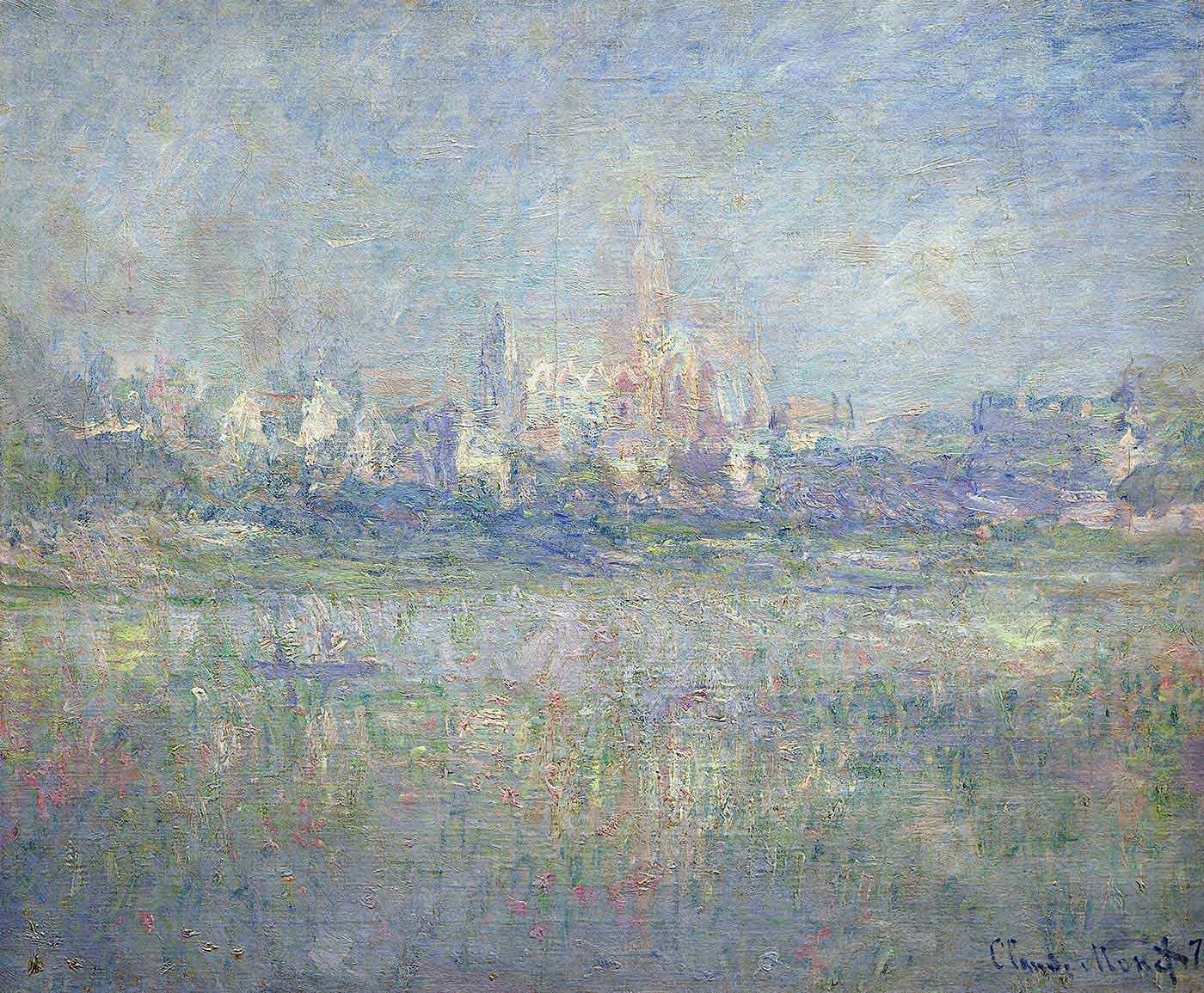

WHERE IS VÉTHEUIL?

Wafts of mist shroud the village of Vétheuil, situated on a hill. There does not seem to be a top or a bottom to the painting, time and space are suspended. There are no picture planes hinting at either fore- or background. Subject and reflection cannot be distinguished.

In the 1870s Monet began to compose his canvasses applying colour in an even and rough manner, which dissolved any order of the elements represented, shifting the focus to the overall structure instead. In the interest of the general atmosphere the artist almost obscures the subject in his work “Vétheuil in the Fog”. The emphasis on the atmosphere is an important requisite for his later serial paintings.

ROUEN CATHEDRAL

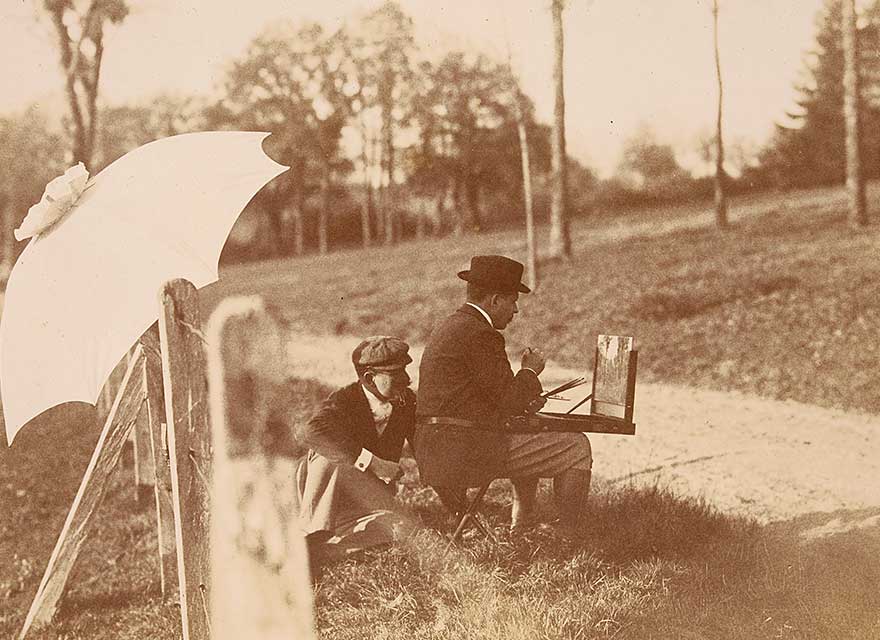

Monet mostly worked on several canvases at the same time. In every weather he took off with his easel and a suitcase with painting utensils. It is likely that he chose to paint the cathedral as its shape, texture and colour would not be altered in the course of the year. It was the weather alone, with its changing conditions of light and shade that would change the atmosphere.

In the studio Monet synchronised the paintings of his series. The artist refused to present or even sell just a single one of his paintings before he had completed the series. This is how important he considered the overall effect to be.

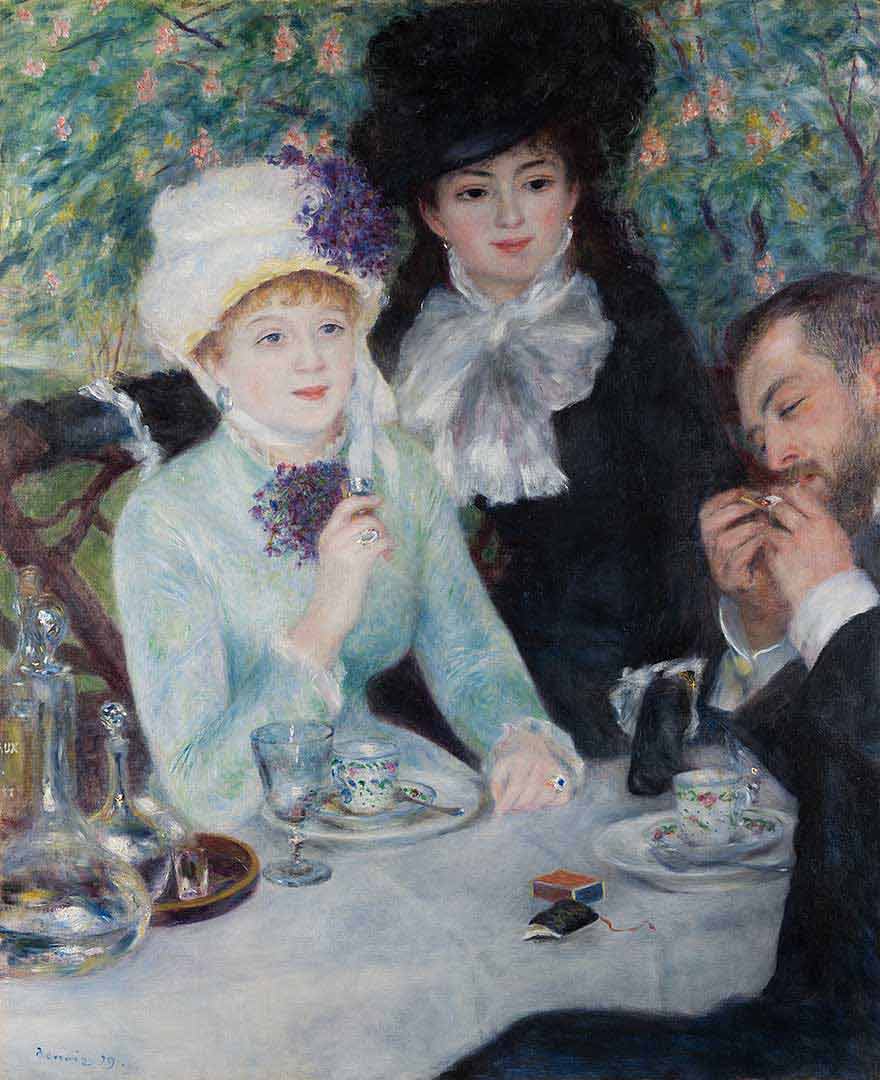

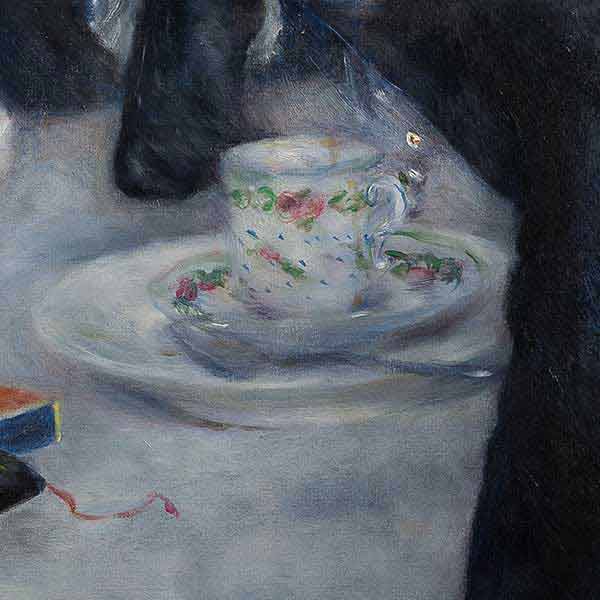

COLOURFUL SHADOWS

What the original betrays

In their paintings the Impressionists paid careful attention to the phenomenon of colourful shadows. In daylight the scattered light from the sky sometimes adds a blue or violet tinge to shadows.

The artists observed that the reflections of light in the surroundings also affect the colour of the shadow. In their works they recorded what they saw. Numerous contemporaries were irritated by the colourful shadows in the Impressionists paintings.

A shadow is neither black nor white. It always has a colour. Nature only knows colour ...

Auguste Renoir, 19106